[Last month saw an argument between Quinns and Matt Thrower, our resident wargamer, over Here I Stand, a game of reformation-era revolution. It might be the nerdiest thing we’ve ever published. This month, we present the debate’s thrilling conclusion! All images in this article are courtesy of BoardGameGeek.]

Quinns: Matt, slow down! I’d never have guessed that a militaristic, paranoid, survivalist maniac would have a house riddled with secret passageways!

Thrower: Don’t forget the booby traps. Have you been treading where I tread?

Quinns: What?

Thrower: Ah, here we are! The heart of my house.

Quinns: It looks like a panic room. Except with a map of the world and… a big, red button?

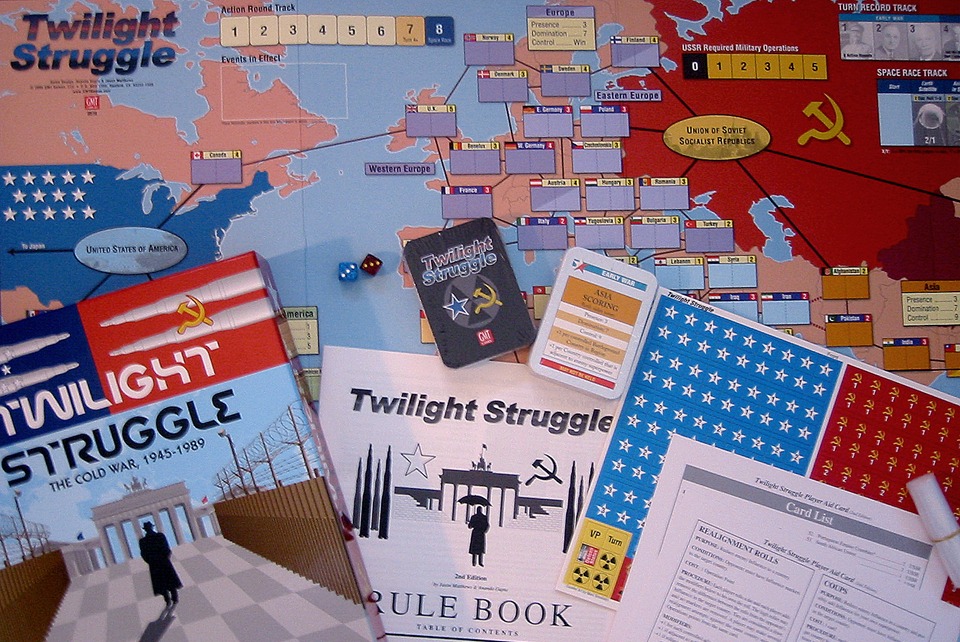

Thrower: Naturally! It’s a room dedicated to my favourite game. Doesn’t every gamer have one? In my case, the game is Twilight Struggle, a card-driven recreation of the cold war and nuclear Armageddon. And, much as I hate to stand with the mainstream, it’s not just me that feels that way. It’s currently the number one ranked game on the global graveyard of game statistics, BoardGameGeek.

Quinns: Ah right. The same top 20 that includes Puerto Rico, Dominant Species and Brass, a game of constructing 18th century English canals. I wouldn’t WANT a good rating in that humourless burg.

Can I press this button, or will it launch a nuclear strike somewhere?

Thrower: Be my guest. It’s not easy to find nuclear missiles on eBay, you know.

Quinns: Matt, what’s all this got to do with my dismissal of card-driven war games?

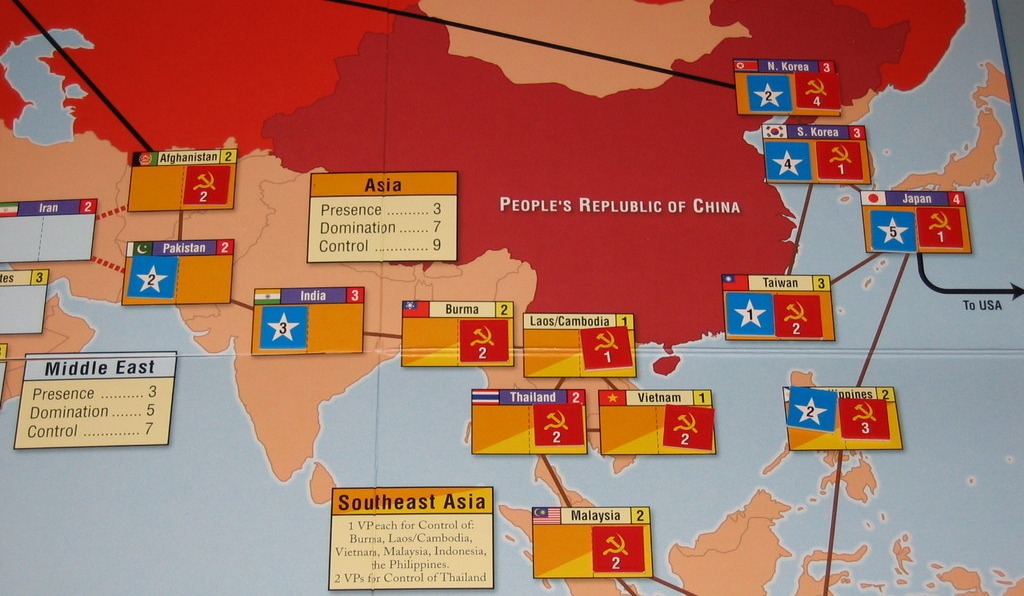

Thrower: Aha! Twilight Struggle is the final evolution of the trend you mention for card-driven games to represent the player as a historical animus rather than an actual person. Here, although the players are ostensibly the US and the USSR, they’re really playing the philosophical spirits of capitalism and communism. The game has become all about political influence, with entire wars devolved to a single dice roll and a DEFCON track.

Quinns: I can play the SPIRIT OF COMMUNISM?

Thrower: Gaze into the face of God!

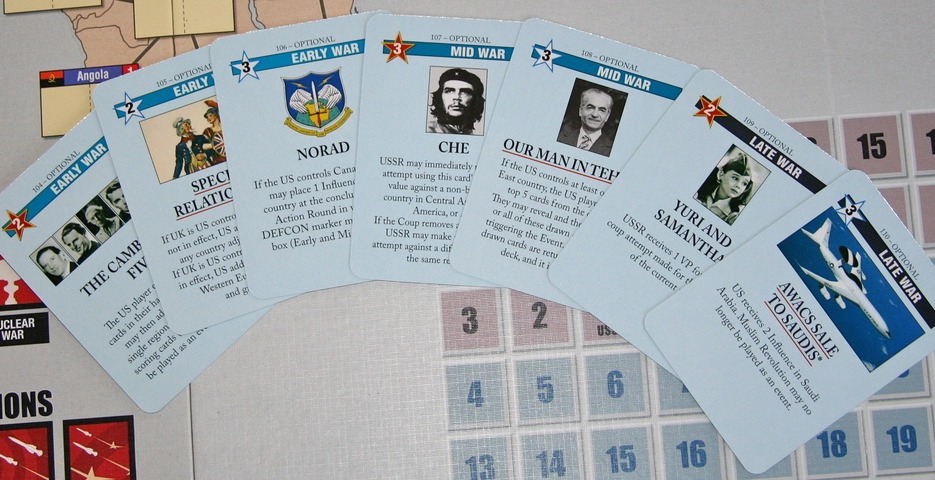

Mechanically, Twilight Struggle is very different from most of its predecessors, and much simpler. It retains event cards benefiting one side or the other that can either be played for the event effect, or a point value to spend on spreading your political influence around. The goal is winning over the majority of countries in each region of the globe.

The genius is that if you play a card with one of your opponent’s events for the points, the event happens anyway. That makes every turn an intricate and absorbing dance where you try and maximise your own events while minimising those of your enemy.

Quinns: No, no! Nice try, but this is all starting to sound like what I hate. I’m still going to be given a hand of cards that look like weeks in a year, and I’ll be playing them in a particular order as if I were some haunted socialist calendar.

Thrower: But all games are about abstract mechanics, regardless of how much detail you pour into them. Do you think playing Campaign for North Africa will really put you in Montgomery’s shoes, planning operations knowing that if he fails thousands of soldiers will die and his country may fall to the Germans? No game can re-create the tension and uncertainty and terror of command. And it least in Twilight Struggle the history has flesh on its bones: you’ll see NATO being formed, the Cuban Missile Crisis, even the election of Margaret Thatcher. Detail way beyond the scope of traditional games.

Quinns: But at least if you’re just pushing chits around it corresponds roughly to decisions that someone, somewhere made. I’m going to press the button again.

Thrower: If you must. Look, one of the key problems with traditional wargames is that they give the player too much information. If you know where all your opponent’s units are then however much of a simulation it is rules-wise, it’ll be nothing like the actual situation. Twilight Struggle, like all card-driven games is more realistic because your opponent’s cards are hidden.

Each turn I’m going through every horrible combination of the cards in my hand and trying to stop the enemy events that I have to set off ruining my game plan. I come up with a strategy to neutralise as many as possible. But mid-turn, guaranteed, he’s going to slap down the one card I really didn’t want to see and I’m back in planning hell all over again. Playing is like having your genitals tickled by Satan’s hellish claw: the most exquisite agony imaginable.

Quinns: But that’s another problem! Because you have no idea what your oppponent’s holding, planning your turn feels like a farce. You’re never really in control, and your enemy’s always going to spend his time changing the playing field entirely.

…I’ve just accidentally described a real war, haven’t I.

Thrower: I’m proud of you!

Quinns: NO. There are other ways of doing the fog of war thing, right?

Thrower: There are others, but they’re generally fiddly and annoying. Whereas in Twilight Struggle and its ilk not only are they part and parcel of the gameplay, but a virtue is made out of the mechanic. There’s astonishing scope for creative strategy. Each card is a wealth of decisions for you to make, about whether you play it for events or points, about how to handle the triggering of hostile events, about how it relates to cards already played or yet to come.

Quinns: At which point you’re not engaging in warfare, or managing a nation. We’ve abstracted it enough that you really are just playing a card game.

Thrower: Of course! The cold war was never about war. It was a long, drawn-out conflict of political ideologies that sometimes spilled over into violence. You couldn’t game this with the usual hex and counter shenanigans: you need a wider, broader system. And it’s important that we game it because these were the formative years of many gamers, and the events continue to shape the modern world.

It’s awful the way so many games shy away from making important statements, wasting an interactive opportunity for learning and discussion. But Twilight Struggle embraces it, shows how brinksmanship became an art and how competing ideologies almost destroyed the world on multiple occasions. You’re often only one card away from the apocalypse and the tension bleeds through into the game itself.

Quinns: Ooh. I like the bit where you justified Twilight Struggle’s #1 spot on BoardGameGeek because of the average age of its users. But we’re agreed that board games really do offer a powerful opportunity for learning, and these card-driven war games seem to do it effortlessly.

I’m going to press the button again. It has a really nice weight to it.

Thrower: Absolutely. Carl von Clausewitz, arguably the father of modern military thinking said “War is the continuation of politics by other means”, and it’s true. Your hexes and counters are good for battles and operations. But strategic games without a political dimension feel empty, the marching jackboots echoing strangely in a half-filled room. Twilight Struggle is the ultimate embodiment, a game spanning decades and many different leaders. It demonstrates that card-driven games work best at a level so zoomed out from the action that the whole of the Vietnam War is represented by a single card, allowing epic detail to be crammed into a three hour game.

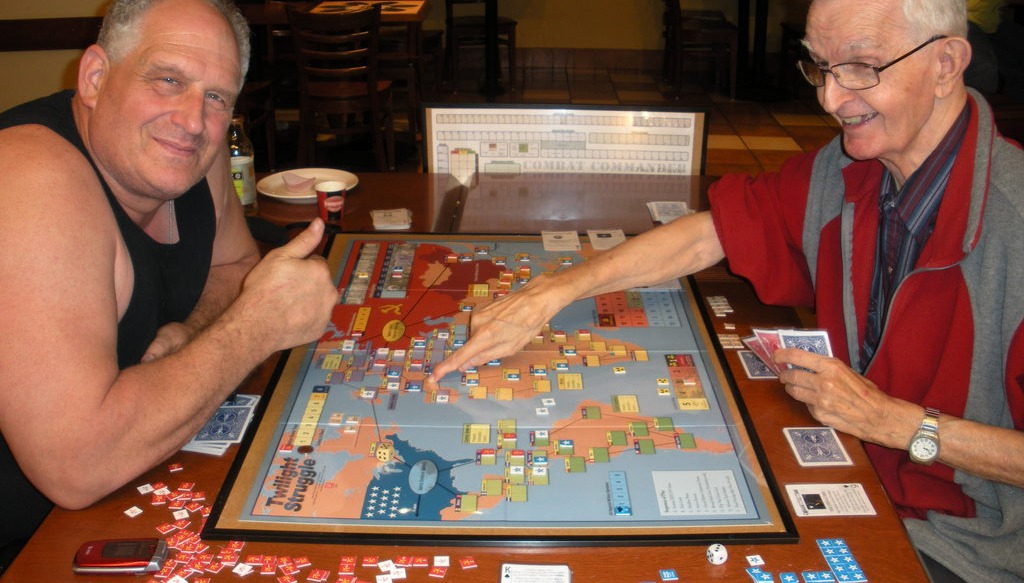

Quinns: You know what, Matt? I think I could get behind that. Shall we play?

Thrower: I don’t think there’s time for that, Mister Smith. We’d better be heading down into the basement. That first button press wiped out most of Kazakhstan, and the second bought hard rain down on the eastern seaboard. The last one launched warheads toward our current location, and we’re at about two minutes to midnight.

Quinns: Very funny. I’m not falling for that! I remember you saying you couldn’t get hold of any missiles for your collection.

Thrower: Oh no. I just said it was hard to find them on eBay, but a certain PartyMember9231 helped me out. I had them wired up to the button for extra realism during play.

Quinns: You’re lying. This is part of the game.

Thrower: Let’s be going, Quinns. Make sure to bring your toothbrush and some aftershave. After all, when it’s safe to come out, the world won’t be repopulating itself!