Ava: Le Havre could be the perfect resource shuffling game. It’s a tightly wound knot of decisions and possibilities, that unfurls and unwraps as you play.

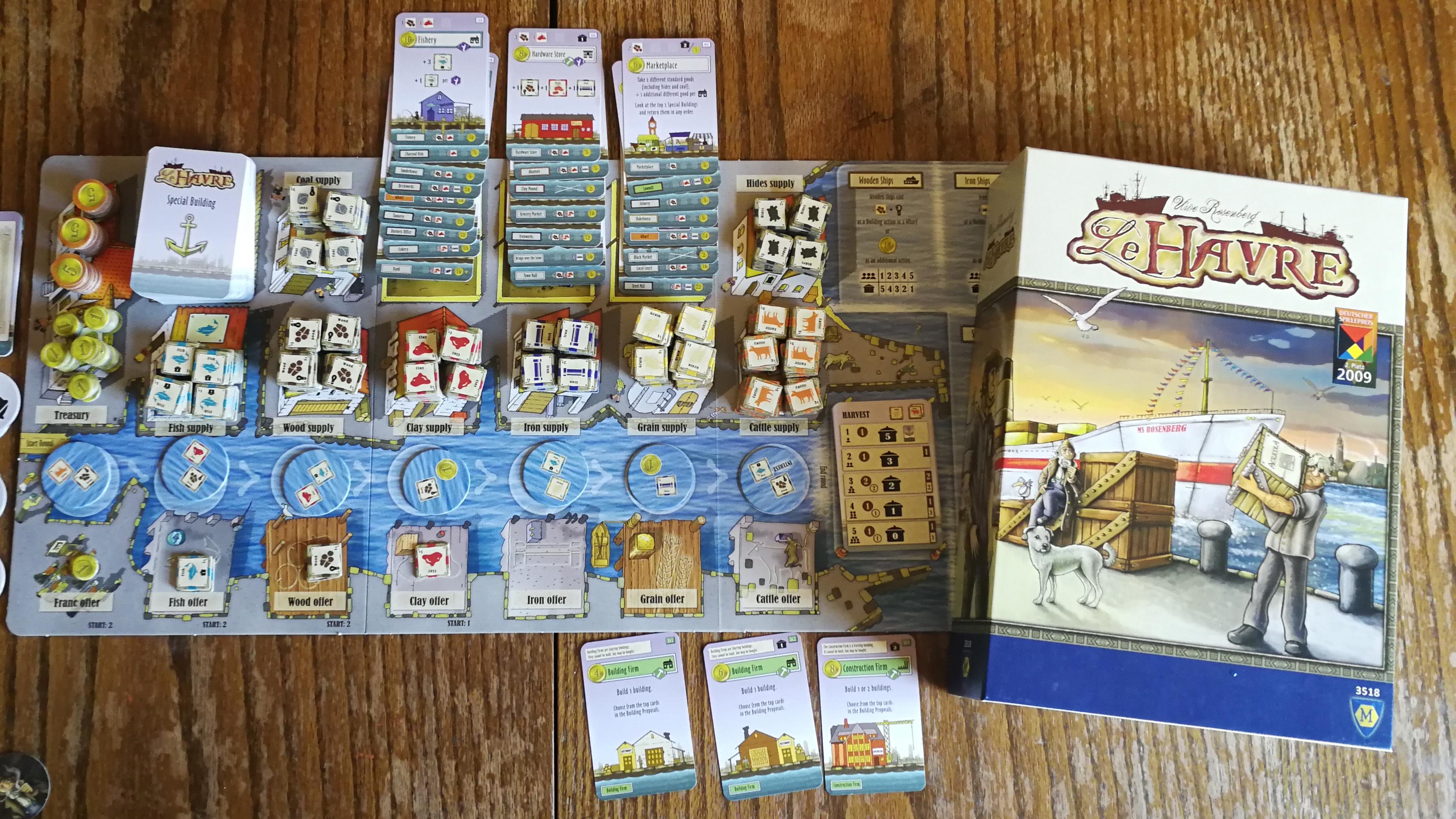

An elaborate and ever-increasing roster of buildings offers ways to process, use, acquire and sell as many goods as you can. Tiny, square, double-sided tokens flood the board, spilling out of warehouses that heave with potential, begging for you to grab them before someone else does.

Each turn is simple. You move your ship to the front of the queue in the middle of the board. This queue keeps track of turn order, and the space you move to dictates what new goods go on the docks, becoming available for anyone to grab. You can then either (a) grab a single pile from the dockside, or (b) you can move your only other piece, a ‘worker’, to a new building card, and use its action.

If another player is sitting in the building you want? Tough luck. You’ll need a new plan.

Coal, hides, cattle, wheat, clay, wood, iron and fish. Each one can be flipped over by the right building, turned into something slightly more valuable or slightly more usable. Everything is worth different amounts of food, money or energy. All three are useful in their own way, until the final scoring, when only money, buildings and ships count for anything. Goods pile up relentlessly at the side of the harbour, available in large dollops at the cost of your turn.

Every few turns, when the line of boats reaches the end of the harbour, you’ve got to feed some food to your ever-growing (and entirely abstracted) family. If you can’t, you’ve got to borrow money to feed them.

That’s kind of it.

Obviously, that’s not it.

The buildings you start the game with let you build other buildings, and once these cards start pouring across the table, they form an elaborate web of interactions and investments. To do anything useful you need to spend several turns bouncing your single worker from one building to the next, burning wood into charcoal, baking wheat into bread, smelting iron into steel, or butchering cattle.

Le Havre is a game of maximisation. The piles of goods get bigger and bigger until someone takes them. There’s always a temptation to leave a stack that you want to grow a little bit taller. It’s a constant lure to push your luck and hope for the best. But be careful, everyone is eyeing up the same ever-growing heaps. And everybody is hungry.

You’ve got to balance yourself between grabbing the goods you need, building the buildings you want, processing what you can sell, and getting stuff ready for the final haul. At the end of the game, everyone gets a single action that can’t be blocked by other players. This normally involves sending all the ships you’ve built to sell all the goods you’re left with. Making sure your fleet is big enough, while holding onto the resources you need to fuel them, and the goods you want to sell? That’s the core of the game, really.

It’s all efficiency, all stacks of stuff shuffling around the board. If you like to spend your time making numbers dance around the table, taking actions that make you feel ingenious for planning ahead, or achingly wrong for falling short by just one piece, then you’ll love Le Havre. It spreads options out before you and asks you to build your own route through them. There’s glory in seeing opportunities, doing the maths, and making it happen.

There are problems though.

The art ranges from fugly to functional to (occasionally) fun, but it looks lovely on the table because of the huge, inviting piles of tokens hiding most of the town. If you’re the sort of player that needs everything in neat tidy stacks, this game might break you, but if you can get behind a reckless heap of cardboard, the harbour has a strange beauty bursting over the seawall.

The building cards line up into neat little seaside villages, and it’s adorable. But it’s scream-inducingly hard to spot the difference between buildings that need clay and buildings that need bricks from across the table. It’s a small detail, but it’s an irritating one. Peering across the table at another player’s pier is a constant struggle.

Teaching is relatively simple, but a huge amount of detail is tucked away on the cards, so you’ll find yourself asking questions throughout the game. The answer is almost always ‘There’s a building that does that, but it hasn’t been built yet’. The manual is well laid out and clear, including a whole page of answers to those ‘how do I do this?’ questions. This is helpful, but I don’t want to hand out an A4 page of small print to someone learning a game unless we’re attempting to simulate a medium-sized war.

The set up is partly randomised, but it barely scratches the core of the game. Each time you play the goods will pile up in a different order and the stacks of buildings shuffle about a bit. There’s a deck of special buildings too, offering big actions or big piles of points. The latest editions of the game come with ‘Le Grand Hameau’ (French for ‘the grand ham’) already in the box. This expansion adds even more special buildings, but you’ll barely see any of them, and they come out too late to truly mix things up.

With this little variety, the only thing to get in the way of building the perfect machine is other people. Someone will absolutely get in your way, take the thing you wanted, or do the thing you needed. There can be ways to get around it, but that’s a big part of the game. Getting blocked. Getting stuck. Getting angry, and scowling while you embark on plan B.

The problem is a lot of this interaction happens without calculation. Someone will get in your way, and maybe they could see what you were planning, but most likely it’s an accident. You’re all in the same race, all in the same lane, sometimes able to pass each other with ease, and sometimes getting jammed up. It’s unpredictable, and it means you can’t play the perfect game. This can give you the urge to come back and make up for your mistakes, but I do wonder how long that can last.

I played it solo, and it was a smooth and simple delight. Without people in the way, you can think as long as you like. There’s absolutely no changes to the rules, so it’s easy to make the switch. The ship and building cards already shift subtly for different player counts, so you’re left with a pure and welcoming version of the game. But after doing it once, I decided I never wanted to do it again. If I got good at it on my own, there’d never be anything pulling me back to the multiplayer, and this is definitely a game I want to put in front of more people. I want to watch my friends get caught in its traps and terrors. I know I’ll get bored eventually, and I want that to come as slow as possible.

Le Havre might be my new favourite Uwe Rosenberg game, but it’s not going to stay that way forever. The designer has made so many different games about collecting resources, turning them into new resources, getting in each other’s way accidentally and adding up points at the end. In some ways, this is the purest take on this structure. It’s hard to argue that a game that could easily run to three hours with enough players is simple, but in many ways it is. You have one decision each turn, it makes one thing happen. Le Havre boils this resource conversion and worker placement into only the most essential elements. But somewhere in that distillation, I know I’m going to get bored of it. The town of Le Havre is always going to be the same town. I don’t think I will ever get the same type of bored with Nusfjord’s nordic ship building (discussed on podcast #86), or Glass Road’s relentless Bavarian resource wheel (BGG page here). The variety in those games is more granular, you’re making your own path, rather than choosing how the steps of the path get revealed.

Uwe knocked it out of the park with this one, though. The bite-sized turns give you time to mull every choice, and remember every mistake for days. It’s a lovely, cruel little trip to the harbour, and it will keep your brain tied up in knots even months after you’ve finished. It’s definitely worth a visit. I’m just not sure I want to move there.