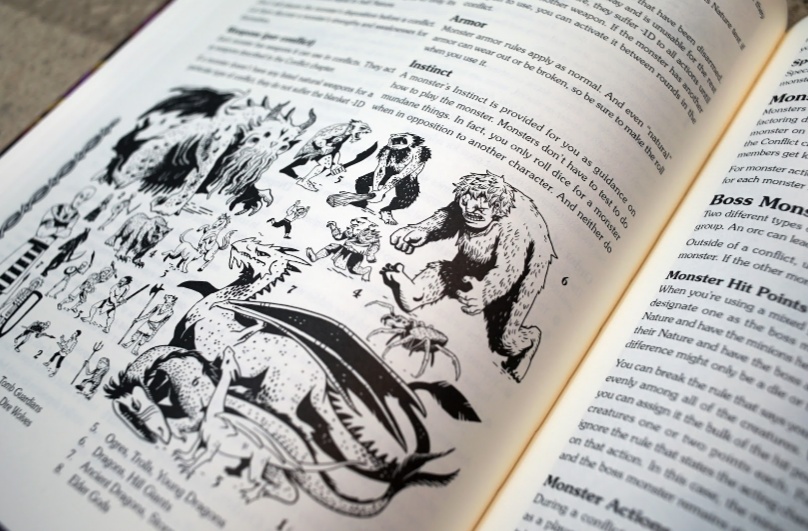

Hilary: Torchbearer is a dungeon-crawling role-playing game.

So what? There are a lot of dungeon exploration games in tabletop roleplaying. It’s the genesis of the genre, and most of the big tabletop RPGs people are familiar with are of this style. One of the things that differentiates Torchbearer is its heavy emphasis on the crawl. While other games are focused on getting loot, fighting monsters, and generally being completely badass adventurers, Torchbearer is about attempting to get loot and deal with monsters, while being completely worn down by the dungeon experience.

It turns out exploring dangerous unknown environments while lugging a bunch of heavy gear and trying to stay hydrated and rested and fed is really, really hard! It turns out there’s only so much space in your backpack and your habit of checking over every room you enter sometimes gets you into trouble and it’s hard to avoid getting cranky as all hell when you’ve been stuck wandering around dank passageways for hours without any snacks.

Torchbearer is based on the Burning Wheel (see my review of that here), via Mouse Guard, but the underlying mechanics take on a very different feeling in this iteration. All three games are from the same design team, though Mouse Guard in particular feels miles from the others in both narrative setting and tone. Torchbearer is ‘crunchy’ in terms of having a lot of mechanics to interact with, though it doesn’t actually involve much number crunching or advanced math.

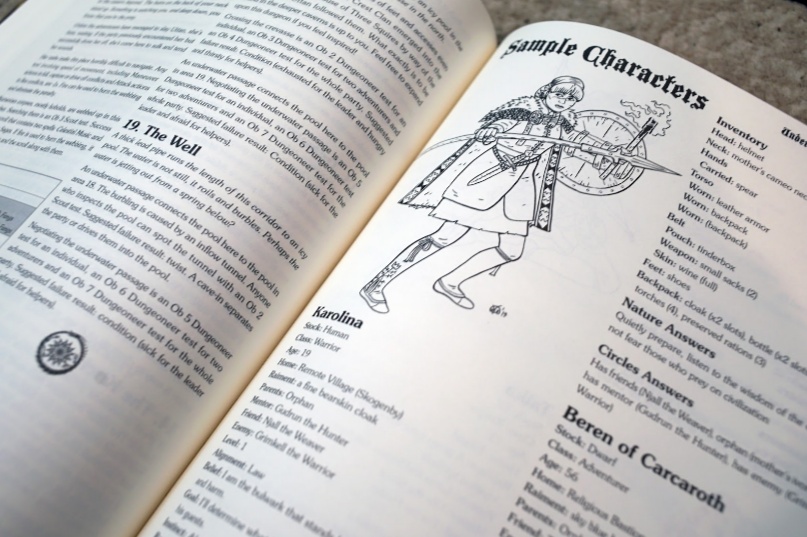

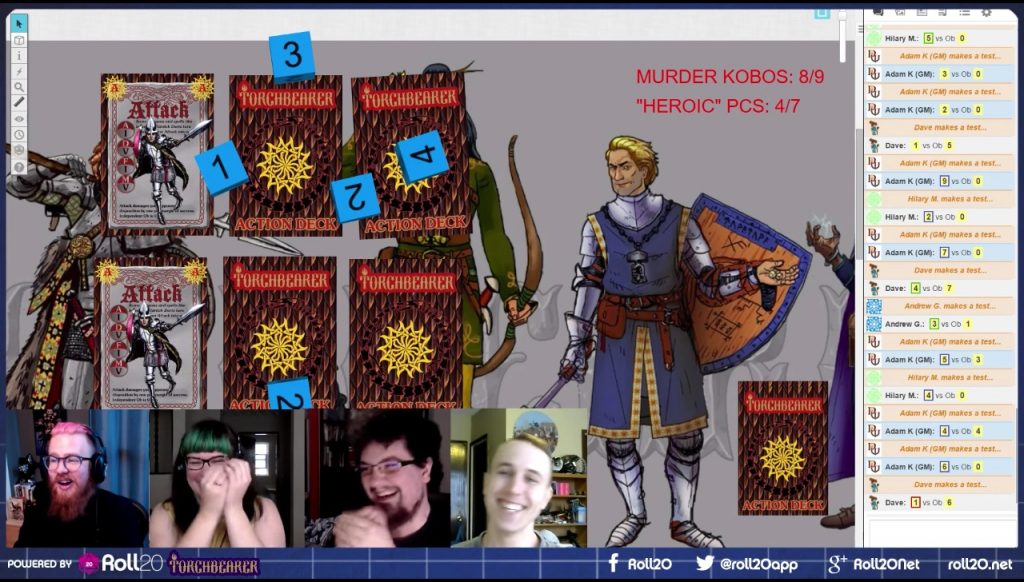

In Torchbearer, as in Burning Wheel, as in life, you start with a limited skillset. And as in the rest of life, attempting to do anything outside that skillset means relying on beginner’s luck and hoping for the best. Unlike regular life, there are also points you can earn by suffering consequences as a result of your personality traits and habits and so on. When your adventuring party enters a conflict you work together to map out your actions in advance (using official action cards, if you have them) with each side then revealing their strategy action by action, round after round—virtually identical to Mouse Guard’s slimmed down conflict rules. Otherwise, the game feels really different to Burning Wheel. And, honestly, unless you’re particularly familiar with the Burning Wheel family of games you may not even pick out those shared system attributes.

The mechanics of Torchbearer can feel a little overwhelming at first glance—the character sheet is involved, there are a lot of blank spaces to fill out and circles to fill—but once you start playing, all the moving pieces come together quite tightly. I sometimes get overwhelmed by and annoyed with highly mechanical tabletop games. When there’s a lot to keep track of it often gets in the way of my game experience, and feels more like a suite of things to mentally hold onto, rather than useful information informing and shaping my game play. In Torchbearer, however, all the mechanics feel purposeful. The game feels thoughtfully designed, with all the moving parts of the larger machine working together to create a gritty, crunchy, real-time realism of the perils and dangers and occasional triumphs of a dungeon delving adventure.

One example is the game’s encumbrance system. Encumbrance in tabletop games generally seems to be handwaved or turned into some sort of abstract and/or highly complicated tracking system. In any of those cases it’s always felt at a bit of a remove from the narrative aspect of the game. Like, okay, I can move 20 feet per arbitrarily-segmented-portion-of-time instead of my previous 40 feet, because I’m now carrying a certain number of coins-worth of weight, but I can still have as many items in my bag as I want? Those sorts of rules are clearly aimed at providing some restrictions and consequences regarding what a character can bring into and out of a dungeon, but I’ve always found them really hard to connect to, either mechanically or fictionally.

The Torchbearer encumbrance system, by contrast, is incredibly explicit, and because of that, incredibly simple. Items can be worn or carried, and your body/bags can only carry a certain number of things. So, you can wear one head-worn thing on your head. You can wear one thing around your neck. You can wear a couple things on your chest. If you’re wearing a backpack on your chest you can’t also be wearing plate mail. A backpack can carry more things than a sack. The order you write things down in your backpack ‘slots’ is the order they’ve been put into your bag. The top item is at the top. If your bag gets a hole at the bottom the bottom item will fall out first.

This seems super obvious, but it is SUCH a departure from how most games handle gear and encumbrance. I know some people find it restrictive, but this mechanic is entirely in line with the realism of the rest of the game. It makes so much sense. And honestly my friends and I have occasionally made use of this explicit, simplified encumbrance system in other games. (To greater and lesser success, of course. Some games are really not made for this sort of realism/specificity.)

Another part of this dungeon-crawling-is-hard-and-you-might-have-a-bad-time realism is The Grind. You enter your dungeon delving adventure feeling nice and Fresh. Pretty soon, though, you end up Hungry and Thirsty, Exhausted, Angry, Sick, and maybe even Injured Afraid or Dead. When things go wrong, or you’re unable to properly rest, the GM can impose or advance your Conditions. Each condition has its own mechanical penalties, of increasing severity, and you can only recover from them in a particular order. For example you can only get rid of your fear if you’ve already dealt with being hungry, thirsty, and angry. And once you’ve lost “Fresh” (the only condition that awards you bonuses instead of penalties) you can’t get it back. Unless you leave the dungeon entirely and go back to town, whatever town that may be.

Torchbearer has specific rules for your time outside the dungeon. You need to find a place to stay, and something to eat, and those things cost money. If you’re lucky maybe you can find a fence for the valuables you pulled from the dungeon—that is if you brought anything back at all. Maybe you didn’t have room in your backpack, or couldn’t carry both a large sack and use your sword. Maybe you have some loot but you end up spending it all sleeping in a tiny room at the inn and a couple of meals. Maybe once you start this life of adventuring you’ll never really be Fresh again.

Torchbearer is full of suffering, make no mistake about it. It’s hard to die, but it’s also hard to get things done. You need to make camp regularly in order to keep your character’s conditions from spiraling out of control. But in order to make camp and do anything during the camp phase you need to spend ‘checks,’ checks you earn by having your traits and habits work against you. And while some people might find this incredibly frustrating, I actually find it pretty fun!

Just staying alive in a dungeon takes work, let alone fighting monsters or recovering treasure. So when you do outsmart a pack of kobolds, or sneak a ring away from some skeletons, or manage to sail a boat back to the mainland without drowning, it feels like a serious triumph. The game is about dungeon crawling on a granular level. You might find a single gem or purse of coins. You might have to leave with nothing but your life and hope your next foray will be more successful. If you didn’t pack enough torches or rations maybe you won’t be able to do much at all.

But the granular, micro-level interactions between the mechanics and the fiction mean that even though you’re likely to get hurt or even killed, it all feels pretty natural. You don’t die for some abstract or arbitrary reason. You die because you feigned when the skeletons attacked, or you never dealt with your injuries and succumbed to exhaustion. The mechanics feel very tied into everything, and that, to me, makes the game enjoyable even when it isn’t going your way. And when it does go your way, it feels so so good!!

As much as Torchbearer sets up its characters for struggle, it does a lot to prime its players for success. It’s a lot easier to roleplay Angry and Exhausted than it is “down to 6 HP,” and the connections, backgrounds, and traits generated during character creation give you a lot to draw on. It is also very much a game you can learn and get better at. The strategy of conflict planning, managing conditions, and even creating optimal characters/adventuring party composition all come with time and exposure and practice. It’s a fantasy dungeon delve, with frequent conflict strategy minigames and relentless multifaceted resource management.

If you play a longer campaign of Torchbearer, you will benefit from your exposure to and experience with the mechanical aspects of the game, becoming a better dungeon delver alongside your character. But be warned, every time I’ve played Torchbearer has been a one-shot, or a potentially open-ended campaign where we all died within the first session or two. Just staying alive in Torchbearer is a lot of work, and deciding to become an adventurer is your first mistake. A mistake very much worth repeating.

Quinns: Coincidentally, Hilary chose to review this at a time when Matt and I were playing a full campaign together! So I’ll just throw in some quick thoughts on Torchbearer as an ongoing campaign.

Torchbearer has actually become my favourite system ever for fostering role-playing on a long-term basis. As Hilary says, there’s a moment-to-moment grind in any of Torchbearer’s adventures, with weapons breaking and monsters encroaching, and “heroes” arguing when to turn back. But once you start stringing adventures together in a campaign, the long-term effects of these systems start to creep up on you.

Your character’s Nature attribute is one aspect of that. Certain characters are naturally inclined towards certain things, you see. Your human might be a natural at boasting, demanding and running, or your halfing might be a sneaker, a riddler, a merry-maker, and you can use a special resource of points to get an outrageous bonus to tests involving your nature. But should you ever fail one of these nature tests, your character is left with a heartbreaking dent to their nature stat. Your human used to boast that he was the greatest fighter that ever lived. Now? No, not so much.

But my favourite rule in all of Torchbearer is to do with your character’s Belief, which is a small, innocuous statement you fill in on the front of your character sheet. Let’s say you believe that “I keep people safe.” Like many RPGs, Torchbearer offers you its equivalent of experience points when you roleplay to that belief. But once you’ve played enough sessions to have that belief set in stone, Torchbearer offers you even more points if you play contrary to it. Et voila! You have a system that encourages character development where your very own beliefs start to flicker and gutter like those torches your carry.

It’s completely ace, and I’ll absolutely echo Hilary’s conclusion. If you like your roleplaying dark and brooding, and it’s been a while since you shanked a kobold, this book is absolutely worth your time.

Matt and I have a nice discussion on Torchbearer in tomorrow’s Shut Up & Sit Down podcast, too. Watch this space!