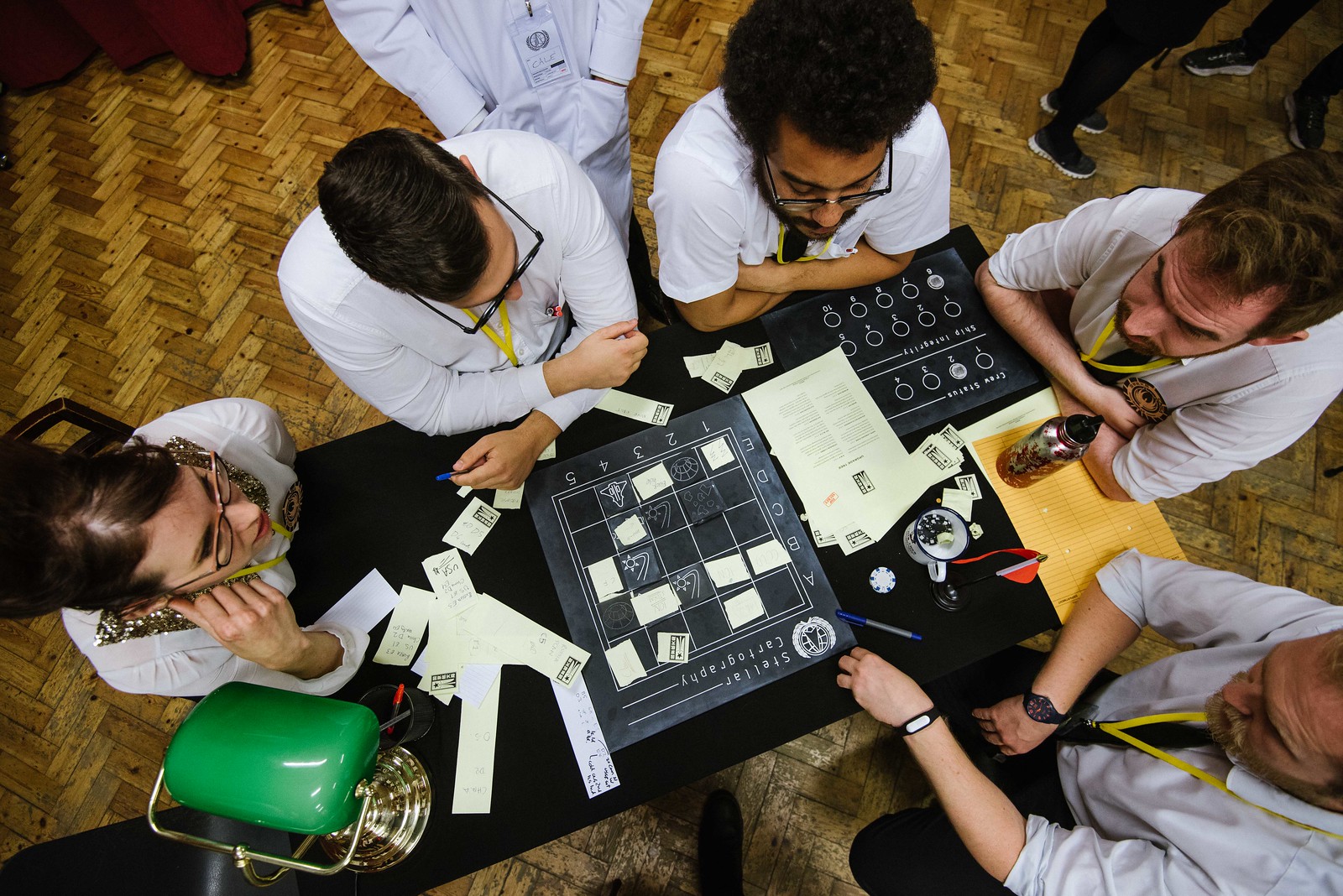

[Special thanks to photographer Ben Broomfield. His other photos of the event are available here.]

Quinns: I’ve never been so excited by the sound of a printer.

Inside the cramped confines of my spacecraft, the machine’s senile clunking makes my heart skip a beat. I drop to my knees, lowering myself before the machine in sweaty supplication. By positioning my head beneath my desk and rotating it 90 degrees, I’m able to start reading the paper before it’s ejected.

The printer is my only lifeline to the three competing space agencies outside my ship – the Americans, the Russians and the Chinese – who are trying to bring me home. Only they have the power to scan the space around me, providing the information that I need to navigate a deadly hellscape of black holes, stars and asteroids. Using their messages, I might just make it back to Earth.

I recognise the Russian insignia on the printed sheet. They’re my most helpful allies. This will be helpful! The printing finishes and I lift it closer to my lamp, banging my head on the desk on the way up. It reads:

“QUESTION FROM RUSSIA: WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE FLAVOUR OF ICE CREAM?”

I gawp at the paper, disbelieving. I’ve been waiting for this message for 15 minutes. I find myself writing my reply without thinking.

“MY FAVOURITE FLAVOUR OF ICE CREAM IS: TWO OF MY CREW MEMBERS ARE DEAD.”

Later I’d find out that their question was chosen as part of a competition among Russian schoolkids, and my answer was read out on the national news. It was not my proudest moment.

This game was Bring Them Home, a new megagame – essentially a room-sized board game – from British company Treehouse. You might remember Shut Up & Sit Down’s role in making the world aware of megagames with our two playthrough videos of Watch the Skies. You might also remember us saying that we were done covering megagames, and instead wanted to find the next big thing.

That was before we heard about Bring Them Home, a design so inventive that we just had to try it. Inspired by The Martian, the game has a single “astronaut” player who’s kept in a separate room. Everybody else is either working for a space agency (and possibly in the possession of a secret objective), or they play the journalists who make frequent briefings to the room, and who give out points to the different countries for good work (like sharing information or bribing journalists). Finally, every space agency can send the astronaut the occasional message, but there’s no assurance that the transmissions won’t be part-garbled when they arrive, leading the astronaut to try and decipher the meaning of the note from every other word.

I was the astronaut. Did I mention that they built me a ship?

They built me a ship. To get in you had to travel up a ladder, down a ceiling hatch and through a crawlspace. When you finally got in there and the game began, you saw this:

Yeah. As far as “My coolest moments in board gaming” go, this was certainly up there.

I’m often asked whether I have any tips for aspiring board game designers. My advice is to bring your existing skills into your game. A shocking amount of SU&SD’s favourite games are made by mathematicians, psychologists, engineers or even philosophers who’ve brought their skills to bear.

If you have the practical skills to build a spaceship with its own electrical hardpoints? Oh my goodness, you should do that. Though actually the ship was just one part of Bring Them Home’s next-level pageantry. The player boards were made from engraved slate, the lanyards were colour-coded, there was music and a dress code. The presentation was stellar (pun very much intended).

As for what else I can say about it, my hands are a bit tied! I can’t “review” Bring Them Home because this was only a playtest of an incomplete version of the game. I can’t tell you the story of what happened, either, because as the astronaut I didn’t really have a story, and me not knowing what was happening on earth was the point of the game. I was trapped in a shockingly sturdy wooden room for three hours, making a series of straightforward decisions based on slips of paper that were sent to me by different space agencies. And while the plot had some twists, I don’t want to reveal them as Treehouse are talking about taking the game to Kickstarter to make it a permanent installation, using the business model of escape rooms.

So instead I’m going to talk about why I found this design so exciting, and what lessons other megagame designers can take away from it. Y’know, besides “Have a spaceship”.

This might be fixed in future versions of Bring Them Home, but as the astronaut my role was functionally reduced to the role of a board game component. I had fun firing text messages back down to Earth, but since I didn’t know who was receiving them I couldn’t conduct a conversation. Equally, the game of flying my spaceship was simple enough that I wasn’t really “playing”, I was just doing what ground control told me to, not unlike a real astronaut.

Sounds bad, right? It wasn’t at all. This role, this design, worked.

For the space agencies their objective was replaced by a literal human being, lending an amount of heart and magic to proceedings that shouldn’t be ignored. Two space agencies would tell me to fly to square B7 and then 20 minutes later the press would announce that my ship had travelled to B7, but having a human do this rather than simply automating it made it curiously exciting. I’d received the message! I’d plotted the course! Every time this happened the crowd of players would cheer so loudly that I could hear them through the walls.

And for the astronaut? It turned out that I was perfectly happy not having much agency, because there’s a huge thrill in being the centre of attention. I got to climb into the ship to everyone’s applause! I got to climb out again when [REDACTED] and everyone [REDACTED]. I knew that tables full of people were all working to get me home, and it was a delight.

I feel like this should be one of those crap headlines from terrible women’s interest magazines. “I was a board game component and LOVED IT! My story on pg. 7”

Bring Them Home also represents an acknowledgement of something that all megagame designers would do well to consider. In large scale games, same as in large companies, communication is, perhaps, the single most important part of the structure. In the case of a megagame you can’t make decisions unless you comprehend the game state, and you can’t know the game state unless you talk. Therefore megagames are ultimately about flapping your gums like (don’t picture this) an industrial gum-flapping machine, and interesting megagames are going to be ones that limit or otherwise play with communication, or at the very least design around it. Frankly, playing the megagames that I have, my single biggest frustration is not having the time to talk to everybody, so making that a game mechanic could be one possible solution.

Remember I said that I didn’t have much of a story to tell? Well, maybe that’s not entirely true. At the end of the game all of the space agencies were telling me to land at their base because they were all hungry for the prestige of me touching down in their facility. This meant that on the final turn of the game they were all telling me that their landing strip was best, or that they’d sabotaged someone else’s, and the Americans, ever-inventive, were even stating that they “had my family”. With the light touch of a sociopath, they cheerily stated that my family “couldn’t wait to see me.”

Faced with the deep-space equivalent of that riddle where you’re faced with two sources, one of which lies and one of which always tells the truth, I began laying out all the messages that I’d ever received, transforming my cockpit into something resembling Russell Crowe’s shed in A Beautiful Mind. By examining all of the messages at once, perhaps I could determine, against the clock, which agency had done the most lying throughout the game. It was absolutely awesome.

But mostly I was only able to piece together the story when the game had ended and I was drinking with all the players. For instance, when life support failed and I lost one of my non-player-crew who was cryogenically frozen aboard my ship, I sent a message back to Earth requesting that someone “name a bridge after her”. She was an engineer, you see.

Upon receiving my message Russia dutifully named a bridge after her. Meanwhile, America tried to one-up them by renaming “all of the bridges”. SCOUNDRELS.

And as we’ve said before on this site, there’s an elegance in designing a game around communication, because it means your game can have simple rules but still be nuanced and complicated because the “rules” are the rules of human communication that we all know already. I quickly decided that I liked the Russians the most, simply because on the tiny slip of paper that they were allowed to write messages on, they wrote in tiny handwriting so they could send me more words. As a lonely starman waiting in the sky, I appreciated all the words I could get.

I don’t want to say any more, partially because I don’t want to spoil it, but partially because anything I say might have changed in the next version of the game. If you live near London and get the chance to play Bring Them Home, you should absolutely give it a try. The best way to find out when and where it’s going to happen is by signing up to the mailing list on their site.

It dawns on me that it’s not that SU&SD wasn’t interested in covering megagames anymore, we were just tired of games about political and militaristic aggression that betray the old-school wargaming roots of an otherwise new and exciting format. With Bring Them Home, it feels like Treehouse games are boldly going where no-one has gone before.

Did I mention it had a romantic subplot? Ah, I’ve said too much…

UPDATE:

As a result of this article I’ve had a short email exchange with one John Mizon of the megagame community. John’s helped me to realise that there are, in fact, a wide variety of non-violent megagames being organised and designed, and I was more than a little ignorant.

I’m having to cherry pick games from the enormous list John sent me, but two upcoming games here in the UK are Colony Mars, a game happening in Cambridge this March about surviving as the first Martian colonists, and Divided Land, a game in London this April dealing with the peace talks in 1947 Palestine.

John made it clear that while many megagames are political, many of them are focused on peace and crisis management rather than war. A few examples are Washington Conference, which sees players meeting as state delegates to discuss ways of easing tension and limiting arms expenditure, Aftermath, a game about working as a shattered government to save a population in the aftermath of an epidemic, and Pirate Republic, a game of pirates and governors that, in John’s experience, saw almost no combat.

John also stated that any number of even more diverse Megagames are currently in development, from Foodies, a game of superstar chefs, food critics and suppliers, to Tooth and Claw, a game of talking animals in the style of Watership Down.

In hindsight, I’d like to apologise for being inaccurate and tactless.

That said, I don’t want to completely back down from my original sentiment. Out of all of the megagames that SU&SD has been invited to in recent years, as well as the ones I’ve seen played at board game conventions, Bring Them Home is the one that reminded me of the dizzying possibilities of the genre.