Matt: Diamonds and bananaaas!

They will slip you up, and please you

They can stimulate and tease you

Bring icecream in the night

and I promise I might DESSERT YOUUU

Quinns: Bananas are forever,

Hold one up and then caress it,

Touch it, stroke it, and undress it,

I can see every part,

And I know in my heart they’re GOOD CAAARDS!

Ba-ba-ba-ba-ba-ba-BABA!

There’s some irony in using a James Bond song to intro one of the least sexy games we’ve ever reviewed. Mombasa isn’t just a weighty, complex game with a fat manual. It’s a game of buying stocks in colonial-era Africa* where one of the areas of the board you’ll be battling is “The bookkeeping track”.

That’s right. Don’t all rush to throw your underwear at the box at once!

That said, if you won’t have trouble inviting your friends over to play with stocks and books, we’re happy to tell you that Mombasa’s puzzle is strong and surprising, like a stinky hippo charging at you out of a river.

Here’s how it works:

Players in Mombasa are racing to have the most English pounds by the end 7 rounds, when you’ll add together the value of the stocks you hold, the coins you have in front of you, and your place on some extra tracks on your personal player board.

Matt: I’ll explain those later.

Quinns: He’ll explain those later.

How do you affect the central map of Africa or your personal board? Easy. You simply select cards from your personal deck, just like in recent SU&SD favourite Concordia, although in Mombasa each round everybody secretly picks 3 different cards to play, then you all reveal them at once and take it in turns to use them.

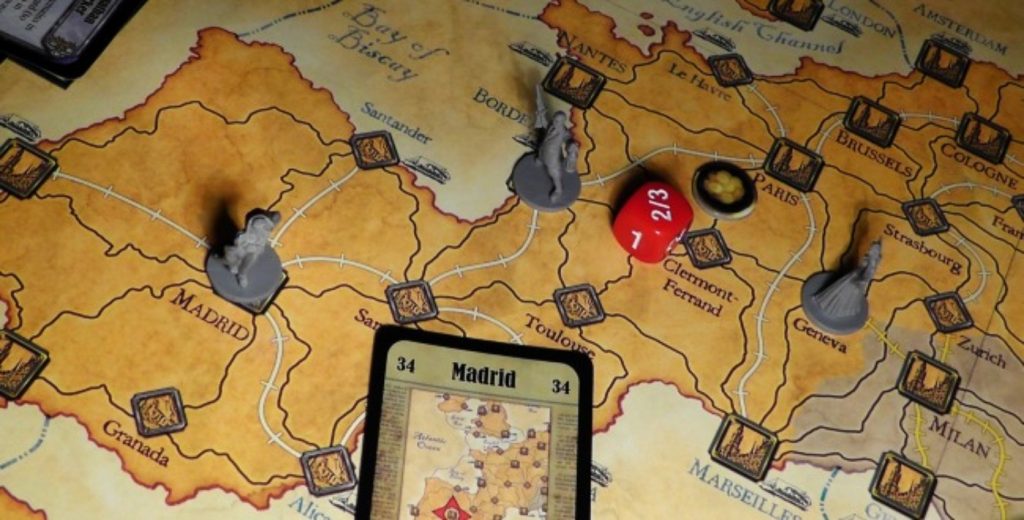

“Exploration” cards give you exploration points, which are how you affect that lovely map. These points can be spent on any of the board’s four trading companies (which aren’t owned by anyone), placing their wooden trading posts on the board as they forge deeper and deeper into the heart of Africa. Importantly, as you pick up trading posts you reveal shiny pounds next to the company’s name, and each revealed pound means the stocks are worth more. So, the more wooden buildings you shovel onto the map, the better the company’s doing. Nice!

What’s less nice is that if you push into territory already claimed by another company, you kick their trading post back off the map, reducing their stock price again. Oh god.

But perhaps you didn’t have aggression in mind. Arguably, the real benefit to exploration is that the board is littered with rewards you can claim each time you pop a trading post into that region.

Another kind of card you can play each turn are “Goods” cards, depicting bananas, cotton and coffee. These let you claim more cards from a sprawling shop. A few cards grant you company stocks, but most simply strengthen your engine for future turns, granting you better Exporation and Goods cards. Finally, Goods cards can also simply be spent launching your little wooden token up the stock track of a given company. Have you got a good feeling about the Cape Town traders? Time to put your dwindling resources where your mouth is. Or, your brain is. Um.

Matt: I really enjoy how flexible the company stock stuff is – if an early investment suddenly looks bad, there’s little to stop you from jumping ship and investing heavily in something different. Two players pushing up the same company’s stock prices might seem fruitless, but a vested interest might be your only hope when everyone else comes to trash your lovely trading posts.

Quinns: It’s kind of amazing that in 5 years of running SU&SD this is the first game we’ve encountered with stock trading. Just as the elephant will one day end up in the boneyard, a hobbyist board gamer will one day buy nothing but games featuring stocks and shares.

Matt: Oh god. I take it all back. Crucially, stocks aren’t your only source of game-winning points in Mombasa: in truth it’s only half of the game.

Diamonds are cool. Did you know that? Diamonds. Cool. We’re all about hard facts and hard stones at the website shut up and sit down dot com. If you want to walk away from the table safe in the knowledge that you’re Mr Mombastic, you’ll need to start thinking about diamonds and books – two individual bonus point-trackers for you to nudge a plastic diamond and a wooden inkwell around, gradually unlocking more points as you do so.

Shooting up the diamond track (you can see it on the left, up there) isn’t terribly exciting, you just need savvy map-control to secure mining outposts and an aggressive tendency to pick up any man who looks like he’ll probably sort you out with diamonds. It turns out that a girl’s BFF is actually book-keeping – a scoring path you have to physically build before you can even use it.

Once you’ve picked up a bunch of books and placed them along your book-keeping path, there’s then no limit to how far you can move up the track in one action. You’re an entrepreneurial frog! You’ve built a super-speed highway out of lily-pad books, and now it’s time to hop your way to the big time. But there’s a catch. It’s a big catch.

Each book shows a set of requirements which you have to be able to show in your currently played hand in order to get past that specific book. The trick here is carefully collecting a bunch of frankly near-identical books: this one needs two coffee beans, done. Next one, two coffee beans and a hat – done. Zoom!

But hubris and books are match made in heaven – it’s all too easy to get cocky and plan ahead, building a track you think can shoot up with ease, only for to you find yourself staring at it two turns later, completely baffled. “I thought I’d have two coffee and a hat this turn?! What was I thinking!”

For a game that’s largely about adapting to what’s being offered on the table, book-keeping is cool because it asks players to honestly guess what kind of game you’re planning to play: either paving the way to your storming success, or remaining useless in front of you as a comedy reminder of the dead, dumb plan you had an hour ago – a personal library you’re unable to access on account of not having enough bananas.

The crucial thing about diamonds and books is that the early stages of both tracks unlock a game-changing bonus, each giving you the potential to play one extra card each round – from a base of three to a maximum of five. This seems good, right? Well, it might be.

My favourite mechanic in Mombasa is the way you get cards you’ve played back into your hand – goods cards played into the slots you use then move up into a discard that mirrors that, allowing you to take back one pile each turn. More card slots mean more discard piles too, and no faster way of getting these cards back – turning Mombasa into a brutal mind-bender.

At this point it’s not just about which cards you play, it’s also about exactly which slots you place them in – effectively rigging up neat little discard piles that are immediately playable as a decent hand. In racing to get five slots as fast as I could, I found myself playing a game that no-one else had to, explicitly planning at least three turns ahead every time I put a card on the table. It was nice to see this heavier style of play available for those who wanted it – even though I didn’t want it when I stumbled in by accident and gave myself a headache.

Quinns: Watching that panic was definitely my favourite part of the game, which is saying something, as I enjoyed a fair few things about Mombasa.

I think what I dug the most was how the game gives you immediate power, letting you spill your influence all over the main board (or your personal one) from the instant the game begins, and the challenges you end up facing are a consequence of what you neglected in those early turns.

I quickly decided I wanted to be King of the Explorers, plunging the titular Mombasa trading house deep into Africa like a banana into a bowl of soft, aromatic coffee grounds. Claiming pre-explored regions cost more, so it made sense to explore the heart of Africa first. Right?

…Well, maybe not. Just like Matt ended up fretting over his cards, I began sweating over stocks. Yes, I’d made Mombasa the most profitable company, but I didn’t own anywhere near enough of it by the end of the game.

I love that. I love making your own rubbish, octagonal bed that nobody else understands, and then having to lie in it with your knees tucked up to your chest. All in all, Mombasa is a good box with a good manual, and a good puzzle with good decisions. It’s good. It’s all good.

Matt: “But” detected, captain.

Quinns: BUT I definitely didn’t like how disconnected the mechanics are. Let’s compare it to Concordia, which is still in my head from our review a couple of weeks ago. Every different action you can take in Concordia drastically affects anything else you might do, creating a complete ecosystem. You make a choice, and that choice will kill and create choices for everybody else.

Mombasa lacks any of that elegance. Whether you buy stocks in a company, acquire diamonds or slide up the bookkeeping track, you’ve simply scored an arbitrary amount of points in that subsect of the game, with no impact on other areas of the board. It’s like a tree falling in a forest. Tying the different tracks in this game together are the rewards printed on different spaces. For example, get this far on this stock track, your bananas will be worth more. Get to here on the bookkeeping track? Get a diamond!

The benefit of this system is that it makes for a humongously complicated puzzle because there are so many teeny factors to take into account, but the downside is that instead of thinking, as you would in a more elegant game, you’re reading the board, adding, comparing. You’re hacking your way through a jungle of itty-bitty benefits instead of being absorbed by theme and colour. And while Mombasa’s fine print might be fitting for a game about bookkeeping, it’s not ideal for a game, full stop.

Maybe if we’d reviewed it last year I’d have been more welcoming? But following on from our glowing reviews of Concordia and Food Chain Magnate, fantastic games which take their depth from player interaction and how their simple systems interact, Mombasa felt to me like the pith helmet on its cover. It’s a bit old hat.

Matt: I agree with that. I do like the fact that this myriad of occasionally-connecting systems allow players to play Mombasa casually (focusing on diamonds and cards), or shoot for something tougher (like bookkeeping and gaining card slots), but you’re right that there’s little sense of anything tying together – the only time where the theme and mechanics really merge is when you’re messing with other people’s stock-prices by knocking key outposts off the map.

I also really liked the forward-planning nonsense of having to manage multiple tiny discard piles that would then form the hand of cards you’d have to use later, but despite the mash of cool ideas there’s little elegance in tying these systems together. It’s not a bad game by any means, but the diamonds and bananas never extend beyond comedy – there’s no sense of theme or role, just things you move around to manipulate systems. For a lot of people that’s probably fine, but with so many hot hot alternatives available it seems remiss to settle for an incomplete package.

Quinns: Yeah. It’s telling that we’ve gone through this whole review, trying to make banana jokes and not quite succeeding.

Matt: Yes, it is.

Quinns: …

*In a sign that times are changing, the unsettlingly warm depiction of British colonialism on Mombasa’s cover is, surprisingly, accompanied by a nervous note from the designer on the front page of the manual. You can read more (and see the note) in this blog post, but it basically sees designer Alexander Pfister reminding the reader that colonialism is linked to exploitation and slavery, and pointing them towards further reading on the subject.