Quinns: If you like comics, we’ve got a real treat for you today!

This month saw the release of the book collecting the first five issues of DIE, a fabulous new comic about a group of people who become trapped in their fantasy roleplaying campaign.

Written by Kieron Gillen, creator of THE WICKED + THE DIVINE, and breathtakingly illustrated by artist Stephanie Hans, DIE quickly became a series where I’d devour each new issue on the day of release. In two words, Kieron describes it as “Goth Jumanji”. In three words, I’d add that it’s “Very, very good”.

What makes this even more exciting is that Kieron Gillen is a personal friend of mine, and agreed to an interview about not just about the series, but the accompanying DIE RPG, and Kieron’s thoughts on roleplaying games in general. This is SU&SD, after all.

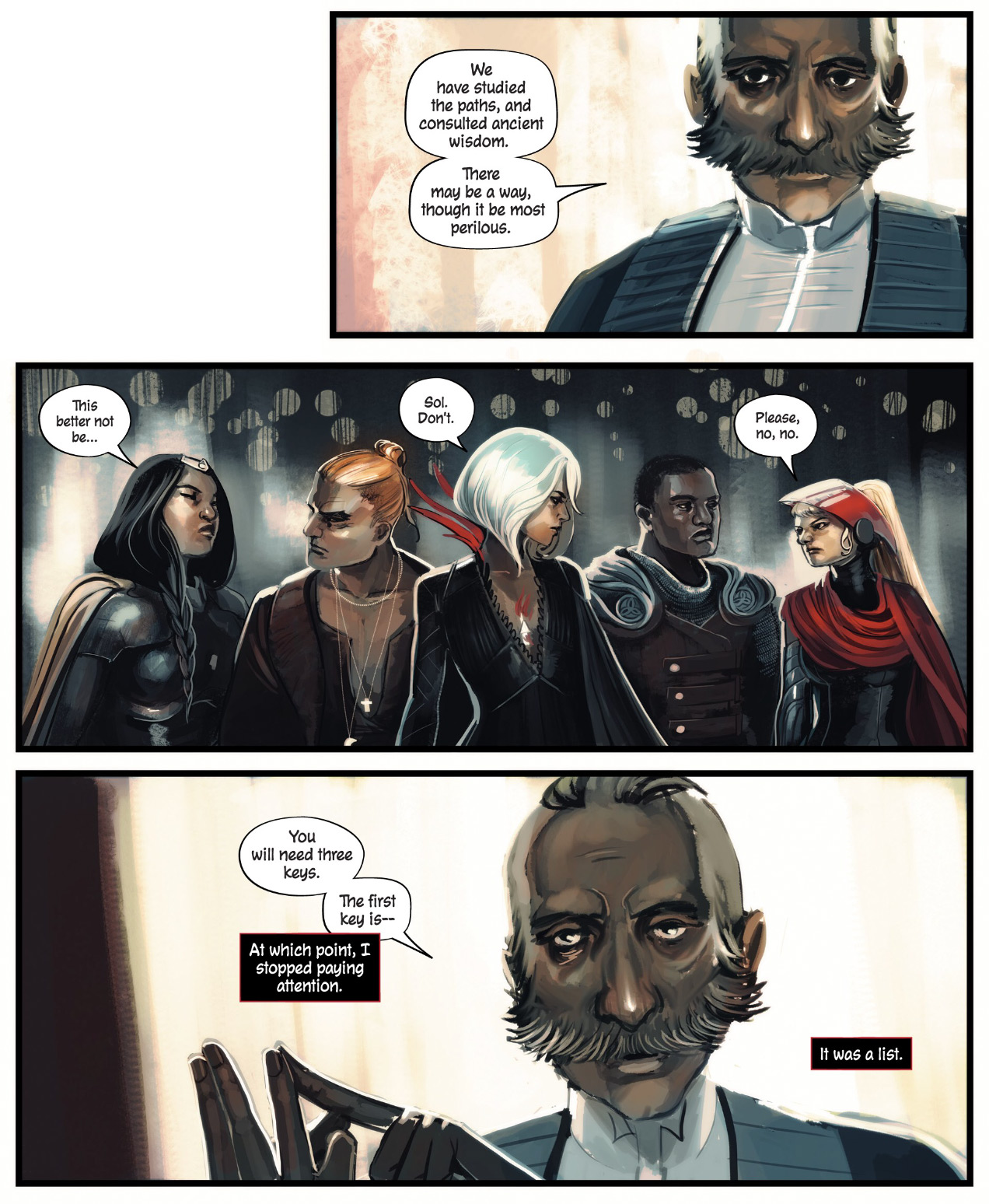

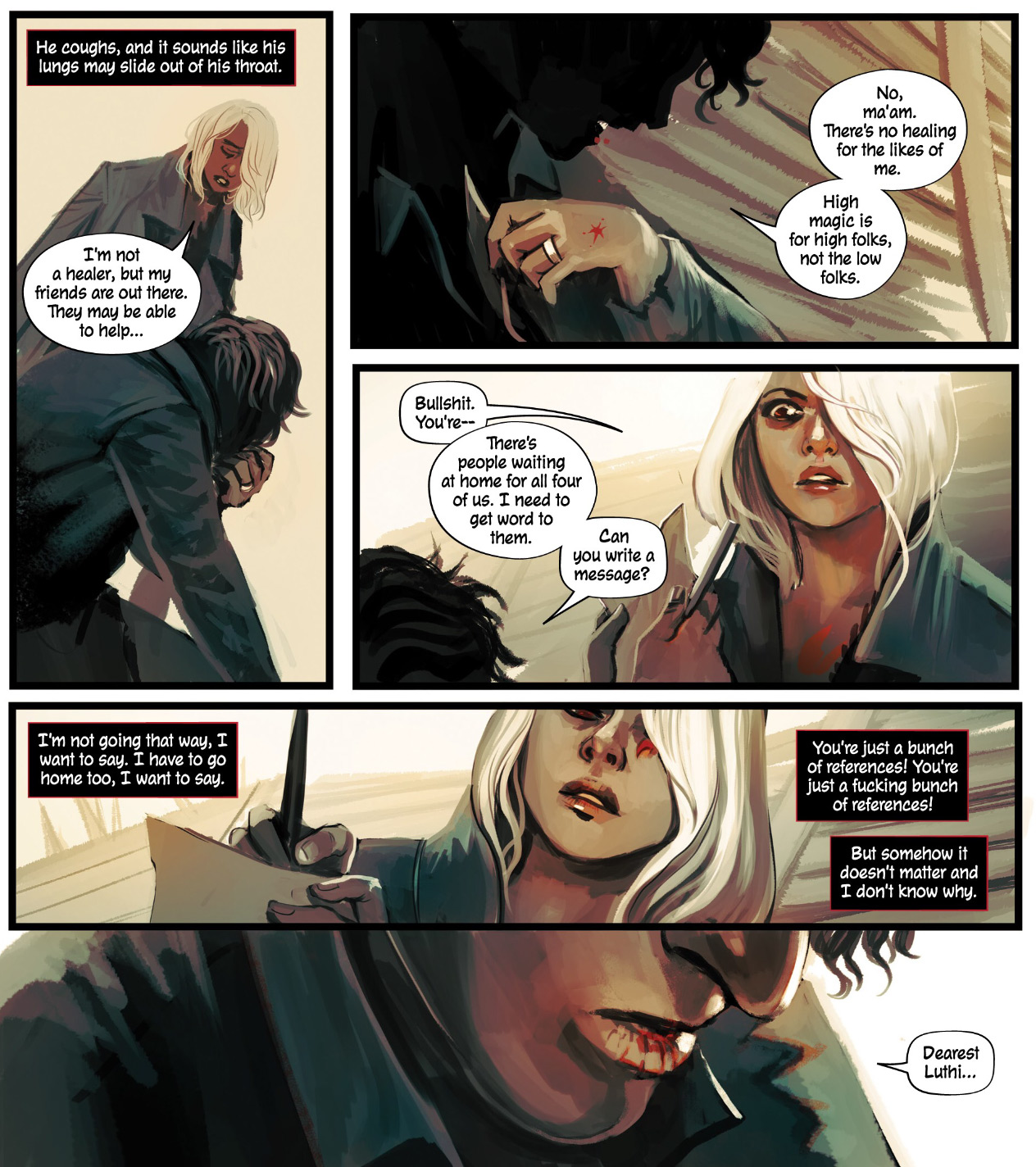

Before we get started, the three preview pages below give a summary of what DIE’s about. Click to see them at full-size!

Quinns: On with the interview. Hello, KG!

Kieron: Hello! Happy to be here.

Quinns: I’ll start with my hardest question. What are your favourite and least-favourite shapes of dice? I warn you now, there are right and wrong answers.

Kieron: The worst dice is clearly the D4. It doesn’t roll. It isn’t natural to interpret in the way that the other dice are. Most of all, it’s essentially a brutal little caltrop that can puncture your feet when it inevitably lands on the floor. The D4 does have some small virtues, however – namely, it looks a bit like a wizard’s hat, so you can put it on top of other, superior dice as an adorable accessory.

Quinns: I actually like how the D4 is a little bit absurd and totemic. I personally think the D8 is the worst. Like the D4, it doesn’t roll properly, but worse, it’s forgettable.

Kieron: The longsword’s d8 damage means I’ve always had an affection for the d8. Plus it looks like two d4’s mid-congress.

I want to say my favourite dice is the D13 that I have and you don’t, because I am like that, but it’s really a toss up between a D20 (which has basically reached the level of cultural icon, and still is a bewitchingly strange object) and D6 (because the common touch counts for a lot). Let’s go for the D20, because its unfolded form is on the cover of the excellent comic DIE, available from all good retailers, etc.

Quinns: There’s a stark contrast between the broodiness DIE’s depiction of roleplaying in the ’90s and the breezy, feel-good nature of the post-Critical Role D&D scene. Did that contribute to you wanting to tell this story?

Kieron: I can’t just have fun. I’d be risking enjoying myself.

Seriously? It’s the mode I’ve always explored as a critic and writer. In Phonogram and The Wicked + the Divine, me and artist Jamie McKelvie were always interested in trying to explore the highs and the lows of pop cultural obsession. That most portraits of pop tend to be about the ups means that including any of the lows makes it appear much more cynical, but I feel that’s mostly contextual. We wouldn’t be so bleak if everyone else wasn’t so relentlessly peppy.

DIE is me and Stephanie trying to apply similar thinking to the role-playing game, and where it’s got us. By which I mean, both as individuals and a culture.

The growth of D&D culture while I’ve been working on DIE has been a weird one. It was already on the upswing back in 2016 when I had the idea, but to see Critical Role invent Stadium D&D has been fascinating. I’ve had moments when I worry that it’s too well timed – it’s clear that someone should do a serious, metacritical examination of roleplaying, right?

On a cultural level, it certainly looks looks like RPGs won. But the thing about winning is that it means you’re now in charge. Geek culture won. It doesn’t need to fight its persecutors any more. As such, it means we can be a bit more honest with ourselves, and talk openly. That’s one of the many terrible things about having to justify your existence to a wider world – in order to defend it, you have to flatten it. In the current state, it’s the perfect time to talk like grown ups about it.

Where did the urge come from? The evening after I had the core idea, I had a moment when I realised why it got stuck in my head. I was wondering whether a part of me has been trapped in a fantasy world, and never got out. At which point, I burst into tears, which is always a tell you’re onto something worth writing about. How has my obsessive love of this hurt me, and all the people around me? What was the cost of all of this stuff you truly love? Hell, why did you love it?

In the same way that The Wicked + the Divine is about “life is short – why be an artist anyway?” DIE is asking a similarly pointed question.

Quinns: Obvious question that you must have been asked before- how *has* your obsession was fantasy escapism hurt you, and the people around you?

Kieron: I haven’t, actually. I suspect the intensity of my answer makes people back away.

Let’s keep it broad and applicable to almost all of us. Look at your life. Can you think of a time when, rather than giving a loved one the attention and time they needed, you were off with a bunch of fantasy people? Be it in a game, either tabletop or video gaming, or almost any form of escapism? This is the writer’s disease, of course – you read enough kids of famous writers talking about being jealous of the imaginary people in their parents heads for the attention they got. This is because DIE is about fantasy in its widest sense.

Quinns: For all of the allegories in DIE, the one that disturbs me the most is the portrayal of the Dungeon Master. Traditionally, the roleplaying community thinks of the DM as a generous or long-suffering figure. In DIE, the DM appears almost inhuman in their desire to escape reality. Where did that come from?

Kieron: The question of “what is the games master” is one of those things which has definitely changed across my life. You say “Traditionally” but I’d say that is something I saw developed. When I was coming in the idea that the DM wasn’t actively antagonistic to the player hadn’t been entire quashed. I remember enough DMs who believed they were there to make the players suffer. Not good suffer. Bad suffer.

Sol, DIE’s DM, was the first character in the book to form, and me explicitly interrogating how my love of fantasy could have stunted me. My one liner for Sol (and it should be stressed, all the one-liners really do reduce the complexity of the cast) is “Peter Pan as serial killer.” He’s the worst possible portrait of myself I can imagine.

There’s more than that, of course – one of the things about winning means we get to play with the imagery that was once used to try and ban D&D. The GM as cult leader, this awful creature. It feels actively wicked to do it, which is a lot of fun.

There’s a line in the rules of the DIE RPG where, towards the end, I compare the DM in DIE to the Goblin King in Labyrinth. “I have done it all for you.” The push and pull between the dominant and the submissive in a GM is fascinating to me.

Quinns: Did a DM ever make you suffer in the ’90s? Didn’t you enjoy it, a little bit?

Kieron: I can’t remember enjoying it. Actual suffering of players is more a sign of incompetence than brilliance. Occasionally of actual sadism. It’s a fundamental lack of interest in the experience of the players. As such, any time I think of what you’re asking, I don’t have anything positive. It’s normally a “I will not be playing with this GM again” moment.

For example, the Rolemaster GM I once played with. We were exploring a castle. That’s what we did all afternoon, room by room. We never found anything in that castle. Anything at all. It took literally all afternoon. Four hours, at least. On the bus home me and the other newest player just glanced at each other in horror. What was that? We immediately set up our own group, because F*** No.

Quinns: I’m cracking up at my desk over here. Holy crap, that’s funny.

Kieron: It was like meeting an alien species who had entirely different motivations than ours.

But in terms of the hard edge to DIE… well, there’ s something one of my readers said when I did something truly awful in one of my comics. “Do not kill Kieron Gillen. If he were to die, it would release the witches inside of him.” Said in a good way.

As a storyteller, people come to me for many reasons, but not least because I play hardball. “Make it pretty, make it hurt” as a retailer has been known to say when trying to sell DIE. As a GM, I tend towards that as well. I want to make people feel something. I want to make the triumphs enormous.

Remember that Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay campaign that you and I played? In terms of what we’re talking about here, the two bits I think of are the bit where you guys just told the Thieves’ Guild where you lived and that you had a lot of gold, and I just smiled, and played out the consequences, step by step. And then the other time, when you were trying to feed a plague quarter. Everyone was starving. For two days, no food. Situation increasingly desperate. On the third day, the outer world sends in a carriage of old parsnips, cabbage and carrots and you guys just cheered. The treasure you guys were most emotionally invested in was some vegetables.

I don’t mean to say any of that is particularly special, but that application of pressure in exactly the way the players want is one of the fun things in that traditional GM/Player model RPG.

Quinns: OK, this is a table gaming site, so let’s discuss you as a GM.

As someone who’s read your comics and roleplayed with you, it strikes me that for all the pain you’re happy to inflict on characters in your comics, as a GM you’re a lot nicer. As your player, I enjoyed regular rewards, and only rarely got the sense that my character was in jeopardy. What makes you interested in nicer stories when roleplaying than in writing comics?

Kieron: Well, it’s unlikely that any of my characters will get up and biff me on the nose if I treat them too mean, and there’s a chance that the players may. You look like you’ve got a jab on you, Quinns.

You’re right. I suspect it’s a weakness of me as a GM, but I do lean avuncular. It’s telling in the example I gave of the thieves’ guild I let you get back to when the robbery was happening so you could chase the thief. A crueller GM would have just cleared you out. More generally though, a lot of that comes from the system you play. In most trad games, I’m not that interested in just offing characters through random dice, so I’m probably too safe. I’m doing story heavy games even during action scenes, so losing a protagonist for no reason doesn’t really seem to be an interesting move. It’s doubly true in games which don’t give any significant guidance of the physical threat a given player can survive, so I’m guessing, and leaning conservative, so combat isn’t that thrilling. In more story-focused systems, perhaps less so – I kill people a lot when running Dungeon World, not least as that Last Breath move is there for a reason. In fact, you came close there, right? That Wizard of yours would have died if you rolled poorly.

(I find myself thinking that while I am too nice as a GM, as a player in a story game, if no-one else is actually causing trouble, I instantly slip into that role. I don’t even enjoy it. It’s just a “Well, someone has to cause some f***ing drama or this game breaks, and I guess it’s going to be me.”)

Which means I am… susceptible to the system? Games seem to have implicit desires in them, and I try to actualise those desires – in fact, I get pissed off when I fail to hit the aesthetic that a game was aiming for. I was heartbroken when running Paranoia for you guys and everyone just decided to pull together in that final scene.

The experience of all that went into the DIE rules – it’s designed to have a particularly mutable aesthetic depending on player input, with all results being good results. It works great as a heroic adventure into another world, but if the players go another way, is a really emotional cathartic cllimax. Hell, DIE is also quite death heavy, for similar Last Breath-Mechanising-Death reasons. When dying is part of the game rather than the end of it, it encourages me to go there.

Suffice to say, I am very happy to kill players if the game calls for it in DIE. The clue’s in the name, after all.

Quinns: Interestingly, what I felt was the cruelest moment from you as a GM in our WFRP campaign was actually my favourite. Do you remember when you tasked us with the command of some soldiers in a hill fort in the middle of a deep, dark forest, packed with Beastmen? And how immediately you made an intimidating situation worse by having the soldiers not respect us?

Kieron: Hah. I can’t remember why they didn’t respect you, for except for the obvious reasons you were all buffoons who had no idea what you were doing. But that is stuff I love – just how you reward the PC with immaterial elements like respect or the opposite. Killing an NPC you like is the most basic form of motivation, but having someone you genuinely like be simply disappointed in you is a wonderful thing. Remember in [the videogame] Deus Ex where all the characters who were likable wanted you to play less violently, and all the s***heads were applauding when you broke out the heavy weaponry? Deus Ex may have given you all the options, but it never pretended that it was equally respectful of all of them. It’s different in RPGs, depending on what you’re buying into, of course.

You mentioning the castle reminds me of someone else who was in that castle. That Elf Ranger walks in and I just describe her as “the most beautiful person any of you have ever seen.” I don’t ever say anything else, or play her as anything other than a competent elven warrior, but it was a joy to see the party of (as far as I know) hetrosexual male gamers turn into blushing schoolboys any time they interacted with her. Sometimes it is very easy indeed.

Quinns: So, now we’ve got an open beta for the DIE role-playing game, based on the comic. Can you talk about how it distinguishes itself from other fantasy RPGs?

Kieron: The RPG, and DIE generally, emerged from a conversation I had with Leigh [Alexander] after we did that WicDiv issue she interviewed the Morrigan for. She said – I paraphrase – “I think your work is most interesting when it exists at the intersection of the bodies of experience that are pretty much unique to you.”

I was obviously resistant to that, but I thought about it, and conceded the point. That issue of WicDiv which was reliant on me being in comics, me being in magazines (both writing for them and editing, commissioning for them), me being in text-based role-play back in the 1990s, and combining all those aspects. It’s not unique, but it is uncommon. After that, I decided to try and explicitly court that in my most personal work.

DIE is the first work post that conversation, and the fact it’s got this whole bloody RPG system hanging off the side speaks to it. That’s what’s unique about it. It’s a system as made by both a critic and a writer, who is simultaneously trying to convert the core of a piece of narrative fiction (which is about games) into a piece of game design (which is about a specific piece of narrative fiction). For a long time I was worried that I was confusing which bit was the dog and which bit was the tail. I’ve come to understand that this is a dog that has ate its own tail, forming a ouroboros. There is no beginning or end, but simply is.

The RPG also has at least four pretty funny jokes.

What we’ve released as an open beta is designed to basically make your very own version of the first arc of DIE. It’s a one off – I suggest running from 2-4 sessions, but I’ve crunched it into one, and know there’s enough content there that people will hack to running longer. If folks like it, we’ll likely do a bigger edition down the line, including all the stuff which we excise from here – full details of the DIE world itself being the biggest obvious omission, though there’s a lot of others.

I think the most striking thing you’ll find, Quinns, is how it basically acts as a Russian Doll structure for looking at RPGs. At each stage, it’s more similar to one mode or another.

First step is a little like a pure narrative game like Fiasco. You sit (including the GM) and generate a social group. In the Beta we advise you to make a social group who (mostly) played an RPG at high school and are getting back together for some event years down the line. Clearly, there’s a lot of flexibility here. A group of 21 year olds getting back together is different from a group of 71 year olds getting back together. This is question driven, and continues until we’ve got a fun social group complete with all the rivalries, loves, hatreds and all those juicy complexities.

You then step away from the table, and when you return you’re acting as your characters (“Persona” in our terminology). This is almost a brief Nordic LARP set up. You sit down at this social gathering, chat a little and… the gamesmaster’s persona gets out a box. It’s an RPG. “You know the urban myth about those kids who disappeared while playing an RPG in the 90s? This is that game. Let’s play it.” Each persona, while staying in character, designs a in-game character.

Third step is, after a little ritualism, each persona is magically dragged into a fantasy world, and likely rapidly transformed into the character they’ve just designed. So you have the player playing (for example) a bitter secondary school divorcee who has been transformed into (for example) a Rage Knight, complete with sentient, murderous Elrician weapon. This is the stage which is most akin to a tradition Arneson/Gygax D&D game, based around the Master playing the environment and everyone else playing their persona. The world they have to traverse uses the fantasy adventure structure, and then adds elements drawn from the players’ backstories, mashed together with the persona’s teenage fantasy game to create this personalised fantasia/nightmare for the group. There’s a lot of techniques I describe for doing so.

The players then either get home, or not.

What I was trying to do is get a really robust structure. As I think I said earlier, it can work as a gleeful Jumanji-esque hack and slash game, and the rules support it. Go there, kill the baddie, go home. Or, with a different group, it can go become a personal piece where people are forced to confront their trauma, and grow (or not). Whichever way the game goes, it holds together.

And the other quiet thing I really like? Despite being as meta as it is, it’s spectacularly easy to role-play your persona. You’re playing a real person in a weird situation. You know what people are like on Earth, and so it’s accessible for people who really have never done something like this before. You don’t know the conventions? You make a persona who doesn’t know the conventions. People who know a lot, can go deep. This is a game that’s often about the fetishism of D&D. Like in the same way the comic highlights the dice as an icon, the game does too.

It’s a lot. I hope people like it.

Quinns: Final question- how could you make Stephanie draw so many sad hobbits?

Kieron: I just had to bribe her with a huge mechanical dragon.

Quinns: Thanks for your time, Kieron. Roll on issue #6!

The DIE trade collecting issues #1-5 is out now, as both a book and on-demand download.